Trigger warning: this review contains discussion of mental health, depression, drug abuse, and suicide.

‘If we knew the antonym of crime, I think we would know its true nature. God… salvation … love … light. But for God there is the antonym Satan, for salvation is perdition, for love there is hate, for light there is darkness, for good, evil. Crime and prayer? Crime and repentance? Crime and confession? Crime and … no, they’re all synonyms. What is the opposite of crime? (…) Crime and punishment. Dostoievski. These words grazed over a corner of my mind, startling me.‘

No Longer Human sat untouched on my shelf for nearly three years before I actually got around to finishing it. Time and time again I read a chapter, found the themes too unsettling, and put it away to gather dust again.

I was right about this, of course; it’s no secret that No Longer Human is not an easy book, nor is it a happy one. Yet at the same time Osamu Dazai’s prose and Donald Keane’s translation come together to create something incredibly beautiful and viscerally haunting.

The 1948 novel is bookended by an unnamed narrator before diving into three notebooks written by Yozo. These external perspectives shape our initial impression of Yozo: he is a social pariah before we meet him, with the photographs of an unnerving young child, a dashing youth, and a faceless old man each reinforcing to the reader that the subject of this novel is far from an ordinary man. The notebooks follow him from childhood to adulthood and trace his decline from a high-achieving student to a morphine addict. in this sense, it’s almost a corrupted Bildungsroman: a coming of age novel, although our protagonist this time never really gets to grips with himself, never successfully or fully becomes a social creature. We are privy to Yozo’s deepest and most intimate thoughts, learning all his ideas and fears—everything that he hides from the outside world. Yozo has from a young age learnt to play the clown, using exaggerated expressions and relentless humor to hide the fact that he ‘lacks the qualifications of a human being’. The novel’s original title, Ningen Shikkaku, translates to Disqualified as a Human Being, and this punishment-like exile is exactly what Yozo thinks defines his existence. His narration feels like both a confession and a suicide note, laying bare his alcoholism, womanizing, fractured family ties, and repeated suicide attempts with an almost masochistic honesty. Because of this, at times, I despised him—loathed him, even. And yet, I couldn’t help but feel a strange, reluctant empathy.

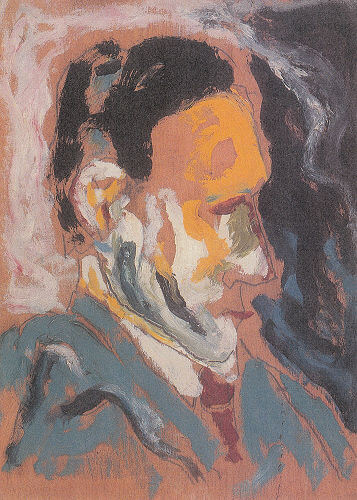

“Self-Portrait” by Osamu Dazai

Dazai’s novel contains almost-autobiographical detail, with some saying he wrote it while suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. No Longer Human was the author’s last published work before his suicide. Some may even take the novel as Dazai’s veiled retelling of his own life through the eyes of Yozo. Both Yozo and Dazai came from wealthy backgrounds but were burdened by guilt over their privilege. They neglected their studies, immersing themselves in Marxism, alcohol, and relationships with prostitutes. In strikingly similar incidents, each attempted suicide by drowning at a beach in Kamakura alongside young bar hostesses—both women died, while Yozo and Dazai survived. Later, both struggled with addiction to morphine-based painkillers. Ultimately, Dazai took his own life by drowning, mirroring his earlier attempt. Yozo’s fate remains uncertain, though he may have met the same tragic end. The result is a scarily realistic look into the mind of a depressed man.

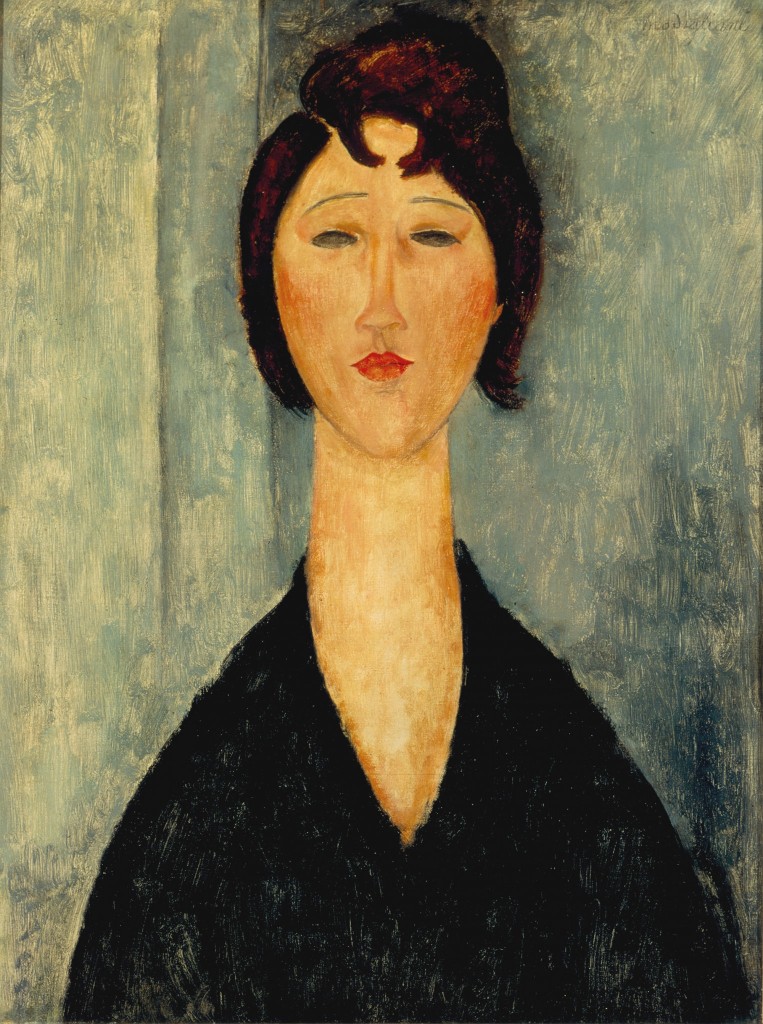

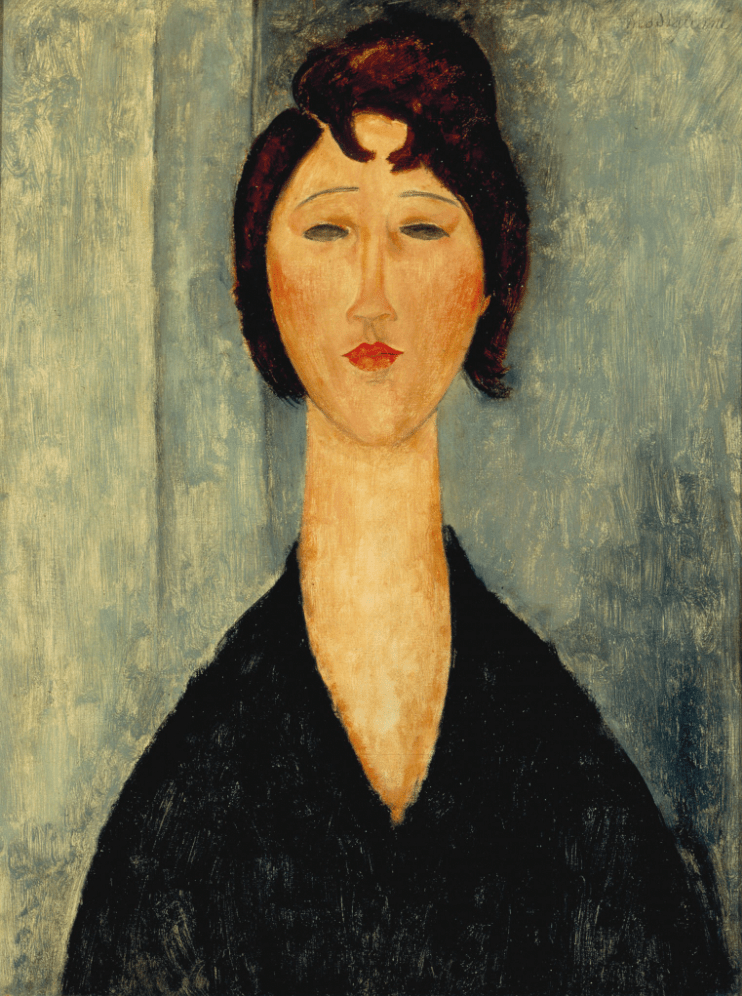

What epitomises Yozo’s character the most to me is his paintings—his so-called ‘ghost pictures’. I was initially puzzled by this name. I couldn’t possibly think of how it aligned with the works of Van Gogh and Modigliani. Yet I came to believe that these paintings are a reprieve from Yozo’s masks and clowning. Unlike his normal pursuit of perfection, his paintings are raw works from his soul, the ghost within him, rather than technical skill and precision. Much like the novel itself, his paintings are a moment where Yozo bares his supposedly inhuman inner workings. When I looked up these portraits of Van Gogh and Modigliani, I understood: yes, there indeed is a ghost-like quality in the sad eyes of these paintings, something that mirrors the melancholy of this novel.

“Portrait of a Young Woman” by Amedeo Modigliani

‘There are some people whose dread of human beings is so morbid that they reach a point where they yearn to see with their own eyes monsters of ever more horrible shapes. And the more nervous they are —the quicker to take fright—the more violent they pray that every storm will be … Painters who have had this mentality, after repeated wounds and intimidations at the hands of the apparitions called human beings, have often come to believe in phantasms—they plainly saw monsters in broad daylight, in the midst of nature. And they did not fob people off with clowning; they did their best to depict these monsters just as they had appeared. Takeichi was right: they had dared to paint pictures of devils. These, I thought, would be my friends in the future. I was so excited I could have wept.’

Yet, I find that what strikes the reader most isn’t the depression depicted, but the feelings of alienation created in a way I have never seen before. Admittedly, I am an unabashed enjoyer of harrowing novels with an unreliable narrator. However No Longer Human is unlike any I’ve read. Yozo is an unreliable narrator but not in the usual self-aggrandised way. Even though he insists upon his inhumanity, the novel is to me, in a strange way, so paradoxically human in its depictions of imperfections. I believe that while it is a bleak, depressing novel, it is not all hopeless. There are fleeting moments where Yozo’s life picks up. Inevitably though, he is thrust back into depression.

Interestingly, to me, the most poignant moments were in Yozo’s descriptions of his childhood. When he describes his loss of interest in bridges and trains when he learns about their practicality, or his complete lack of desire to eat, I thought: Yes, this is a man, who is not human. He has no appetite for life. Of course, Yozo learns to blend in, but these early memories of a sickly boy who is shaped by emotional isolation and abuse by his servants create an indelible distance, a separation that enables some fascinating contemplations on what it means to be human. What is the part of our psyches that cause us to act the way we do? Are we truly selfish creatures? Are we guided by a desire to please others? I found myself reading page after page with a sense of morbid fascination. I wanted to see the depths of this man’s mind—every single thought because frankly, some of them aligned with my own. Indeed, I found myself relating to that sense of gnawing ‘otherness’ that Yozo describes.

We do not know where Yozo ends up. The novel closes with a Madam placing Yozo’s faults on his father: “[Yozo] was a good boy, an angel.” This was disingenuous and cynical to me—a hollow epitaph for a man who lived his life believing he was a monster. It’s a final act of erasure, reducing Yozo’s suffering to a simplistic blame game rather than acknowledging the profound alienation that defined him. There’s a cruel irony in how even in his absence, Yozo is misunderstood, his humanity denied once more. I’ll admit: the ending wasn’t fully satisfying to me, but I believe it was meant to be this way. The ambiguity feels deliberate, a final refusal to grant the reader—or Yozo—the closure we crave.

I am glad I read this book and the reflection of humanity it offered, one that I was perhaps not fully prepared to look into. That said, I would highly recommend this book to those who are prepared to read it, the ones who are willing to face its unflinching gaze.

Leave a comment