Privilege, when destabilised, shows its hollowness—a truth depicted by both Virginia Woolf in Mrs. Dalloway and F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby. Indeed, in both novels the upper classes experience a growing disillusionment when the stability and privilege of their lives are disrupted by changing circumstances. While Mrs. Dalloway is set in London and The Great Gatsby in New York, both novels are rooted in the 1920s—a post-war era of unprecedented change. This upheaval manifested in the overturning of gender dynamics, the decline of religion, the weakening of the Conservative Party in London, and the Jazz Age’s promotion of consumerism and the nouveau riche lifestyle. Dr. Madeleine Davies refers to 1920s London as a “country with an identity crisis,” a label equally applicable to America despite its superficial decadence contrasting with England’s post-war instability. England’s crisis stemmed from the crumbling remains of war: bankrupt aristocracy, shell-shocked veterans haunting the streets, and an empire fraying at its seams. America’s crisis, meanwhile, was born of excess: the Jazz Age’s glittering consumerism, prohibition’s underworld, and the American Dream’s collapse into unbridled greed. The old-money elite in both nations clung to eroding hierarchies, but where the British mourned their loss, Americans drowned theirs in champagne. America’s booming capitalism bred skepticism toward the American Dream, which John Truslow Adams vaguely defined as “a life better and richer and fuller for everyone” (a phrase that shows how illusory the Dream was in itself), while the British stewed in skepticism about the very fabric of society and the expanding dominance of the working class.

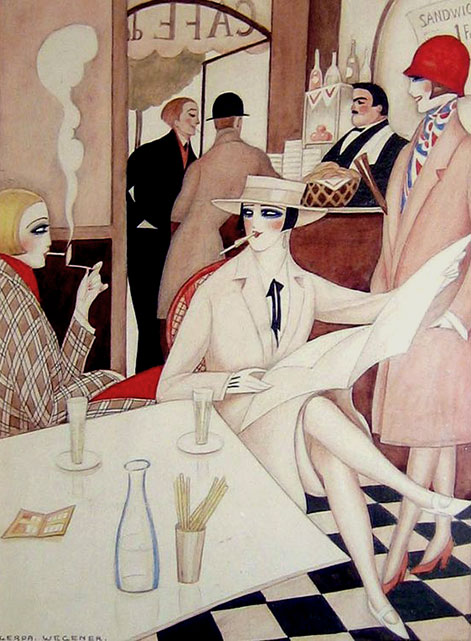

Artworks (left to right): London in the Rain by Anthony McNaught and Café by Gerda Wegener.

Ironically, it is in capitalist excess that the upper class of The Great Gatsby comes face to face with the reality that money cannot buy happiness, a complete uprooting of the power and status of the old-money class. When Daisy reunites with Gatsby for the first time, he ostentatiously displays his collection of shirts, prompting her to ‘cry stormily’ and remark that ‘They’re such beautiful shirts,’ while sobbing, ‘her voice muffled in the thick folds’. Despite what seems like a trivial matter, she states that it ‘makes her sad because [she has] never seen such — such beautiful shirts before’. The emotional language and lexical field of sorrow (‘sobbed’, ‘sad’ ‘cry’) juxtapose the triviality of an item like a shirt. Daisy associates grand displays of wealth with strong emotions such as love or sadness, yet, a shirt is something external and removable, and able to be acquired through simple purchases. This portrays a tragic, yet absurd and almost humorous scene that highlights the shallow, money-driven nature of the upper class. As Ray Cluley argues, Daisy represents a ‘promising land [that] was in fact corrupted by wealth,’ and this is especially true when it comes to her perspectives on matters. This is further evident when she says ‘Oh, you want too much!…I love you now — isn’t that enough? I can’t help what’s past’. The fact that she sees grand purchases as simple matters while Gatsby asking her if she loved him is ‘too much’ shows that wealth has offered the upper class a blanket of security; when removed, people like Daisy find themselves breaking down, as seen by her fragmented syntax. She is facing the fact that money cannot stop her marriage, family, her love for Gatsby, and any sense of stability from falling apart, and the simple monosyllabic statement of ‘I can’t help what’s past’ reads like a declaration of defeat: the world around her is collapsing while she is unable to reconcile love and the impermanence of her privilege.

Artwork: The Great Gatsby by Kate Baylay

Like Daisy, Clarissa has chosen stability over passion by marrying Richard, yet she too comes to a point where she begins to doubt the emptiness of the aristocratic lifestyle she leads. Woolf writes that Clarissa feels ‘the oddest sense of being herself invisible; unseen; unknown…not even Clarissa any more, this being Mrs Richard Dalloway.’ The asyndeton of ‘invisible; unseen; unknown’ implies a complete loss of identity. She is a woman reduced to a title – that of her husband’s name. Despite her lavish parties and Richard’s political status, Clarissa is haunted by mortality and powerlessness, a thought that further threatens to undermine her marriage. Clarissa’s clinging to the past is evident when she says, ‘He’s enchanting! Perfectly enchanting! Now I remember how impossible it was ever to make up my mind—and why did I make up my mind—not to marry him?; The immediate exclamatory phrase of his ‘enchanting’ nature (where enchanting also implies something dream-like and illusory) reflects a yearning for a more beautiful time. Nevertheless, the repetition betrays her desperation to recast a memory, and perhaps even her straining to convince herself. She is quickly hit by reality and regret, underlined by her disordered speech and rhetorical questions. Peter, who carries pocketknives and cries openly, represents everything Richard Dalloway is not—unpredictable, emotionally alive. Thus, he is terrifying to a woman who has built her identity on social performance. Their reunion forces Clarissa to evaluate the cost of her marriage: stability in exchange for a slowly suffocating invisibility and lack of purpose. Peter represents a road not taken and a past that when reflected on, makes her feel a growing sense of disillusionment towards the illusory social expectations she lives under. Her past undermines the stability of her life, reflecting the broader upper-class anxiety in a decade where social certainties crumbled.

Leave a comment